Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is something that was first written about by Dr. Leon Festinger. The implications for those that follow William Branham is that they are becoming more fervent in their beliefs and behave more like a cult as a direct result of the work of this website and others like it.

Prediction

Because of the mass of evidence that has been produced by this website and others like it, cognitive dissonance will cause an increase in fervency of message believers. This will result in the message becoming more cult-like. Those in the message who are Christians will start to leave the message which, in turn, will cause the message to become even more cultish. This prediction was made on December 10, 2012. Please note that this is a prediction and not a prophecy.

Definition

In 1956, Dr. Leon Festinger wrote a book entitled, "When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World". Here is a quote from that book that describes perfectly what happens when a message follower is confronted with evidence that William Branham's visions failed:

- A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.

- We have all experienced the futility of trying to change a strong conviction, especially if the convinced person has some investment in his belief. We are familiar with the variety of ingenious defenses with which people protect their convictions, managing to keep them unscathed through the most devastating attacks.

- But man's resourcefulness goes beyond simply protecting a belief. Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief and he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervor for convincing and converting other people to his view. [1]

Cognitive dissonance is a term used in psychology to describe the feeling of discomfort when one is confronted with facts or information that is in conflict with a firmly held belief. In a state of dissonance, people may sometimes feel "disequilibrium": frustration, unsettled, dread, guilt, anger, embarrassment, anxiety, etc. And this feeling isn’t just in our minds; it creates measurable physical tension which can result is us actually feeling ill. Cognitive Dissonance - Wikipedia</ref>

In the 1950s, Leon Festinger proposed the theory of cognitive dissonance. Festinger observed that when a person held a belief that was later disproved, the individual held the belief more strongly afterward if certain conditions were present.

Cognitive dissonance theory is simple. An individual holds a particular strongly held belief (e.g., I believe that William Branham is a prophet). They are presented with clear evidence to the contrary (e.g. some of William Branham's visions failed). Conflicting information creates dissonance, a state of anxiety that the individual is motivated to reduce or at least not increase. The mental distress causes changes in the individual’s behavior (e.g. getting angry) or beliefs (e.g. the believe the message more strongly). They may also seek limit exposure to the negative information (e.g. they stop reading this website).

The amount of dissonance indicates the importance of the beliefs to the person. Beliefs that are held strongly are capable of arousing more dissonance than less important beliefs.

Dissonance may be reduced by changing behavior, altering a belief, or adding a new one. When the person makes a decision where the alternate choices each have positive and negative aspects, dissonance may result from the decision.[2]

Not everyone feels cognitive dissonance to the same degree. People with a higher need for consistency and certainty in their lives will probably feel the effects of cognitive dissonance more than those who have a lesser need for consistency.

Cause and Effects

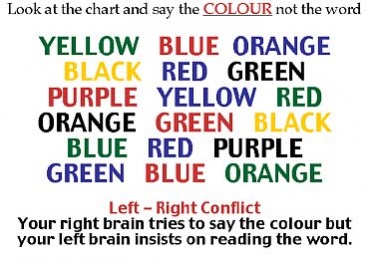

Dissonance is created when your brain attempts to process information that is inconsistent with other information that it holds to be true. This can be as simple as the example of the color chart on the right or the much more difficult dissonance that results when information is received that is opposed to a person's fundamental beliefs.

Most people will avoid situations or information sources that give rise to feelings of uneasiness, or dissonance. If this uneasiness is not reduced by changing one's belief, the dissonance can be resolved by misperception, rejection or refutation of the information, seeking support from others who share the alternative beliefs, and attempting to persuade others.

Cognitive dissonance leads people to accept any information that affirms their already established opinions, rather than referencing material that contradicts them. For example, a person who is politically conservative will only read newspapers and watch news commentary that is from conservative news sources. This bias appears to be particularly apparent when faced with deeply held beliefs, i.e. when a person has 'high commitment' to his or her attitudes.

The process of attempting to eliminate cognitive dissonance is referred to as dissonance reduction. Many Message Believers deal with the dissonance created by William Branham's failed prophecies by avoiding websites like this. A number of Message Ministers have supported this approach by preaching that members of their churches should avoid the internet altogether.

Conditions required for increased fervency of belief

Festinger stated that five conditions must be present if someone is to become a more fervent believer after a failure or disconfirmation:

- A belief must be held with deep conviction and it must have some relevance to action, that is, to what the believer does or how he or she behaves.

- The person holding the belief must have committed themselves to it; that is, for the sake of their belief, they must have taken some important action that is difficult to undo. In general, the more important such actions are, and the more difficult they are to undo, the greater is the individual's commitment to the belief.

- The belief must be sufficiently specific and sufficiently concerned with the real world so that evidences may unequivocally refute the belief.

- Such undeniable disconfirmatory evidence must occur and must be recognized by the individual holding the belief.

- The individual believer must have social support. It is unlikely that one isolated believer could withstand the kind of disconfirming evidence that has been specified. If, however, the believer is a member of a group of convinced persons who can support one another, the belief may be maintained and the believers may attempt to proselytize or persuade nonmembers that the belief is correct.[3]

Examples

The Fox and the Grapes

A classic illustration of cognitive dissonance is expressed in the story, "The Fox and the Grapes", one of "Aesop's Fables". In the story, a fox sees some high-hanging grapes and wants to eat them. When the fox can't think of a way to get to them, he decides that the grapes are probably not worth eating, with the justification the grapes probably are not ripe or that they are sour (from which we get the common phrase "sour grapes").

This example follows a pattern: one desires something, finds it unattainable, and reduces one's dissonance by criticizing it.

UFO Cult

Festinger studied a religious group that predicted the world’s end on a particular day. Anticipating the end, which included a daring rescue from outer space, they sold all possessions and waited on a mountaintop. When the predicted end and rescue failed, they held their beliefs more strongly. These findings stimulated Festinger to examine the cognitive and social factors in belief and behavior change.[4]

In the summer of 1954, Festinger was reading the morning newspaper when he encountered a short article about Dorothy Martin, a housewife in Chicago who was convinced that the apocalypse was coming. Martin had experimented with automatic handwriting and started getting messages from an extra-terrestrial from the planet Clarion a few years before, but now the messages were getting eerily specific. According to the alien, human civilization would be destroyed by a massive flood before dawn on December 21, 1954.

Martin’s prophecy soon gained a small band of followers. They trusted her messages, they had left jobs, college, and spouses, and had given away money and possessions to prepare for their departure on a flying saucer which was to rescue the group of true believers, who called themselves the Brotherhood of the Seven Rays.

Festinger realized that the Brotherhood of the Seven Rays would make a great research subject and infiltrated the group by pretending to be a true believer. Festinger wanted to study the reaction of the cultists on December 21, when the prophecy failed.

On the night of December 20, Keech’s followers gathered in her home and waited for the aliens to appear. Midnight inexorably approached. When the clock read 12:01 and there were still no aliens, the cultists began to worry. A few began to cry. The aliens had let them down. But then Keech received a new telegram from outer space, which she quickly transcribed on her notepad. “This little group sitting all night long had spread so much light,” the aliens told her, “that god saved the world from destruction. Not since the beginning of time upon this Earth has there been such a force of Good and light as now floods this room.” It was their stubborn faith that had prevented the apocalypse.

They faced acute cognitive dissonance: had they been the victim of a hoax? Had they donated their worldly possessions in vain? Most members chose to believe something less dissonant to resolve reality not meeting their expectations: they believed that the aliens had given earth a second chance, and the group was now empowered to spread the word that earth-spoiling must stop.

Although the prophecy had failed, the group was now more convinced than ever that the aliens were real. The group dramatically increased their proselytism despite the false prophecy, sending out press releases and recruiting new believers.

This is how they reacted to the dissonance of being wrong: by being more sure than ever that they were right. They were so committed to their beliefs – they had so much invested in the idea that the world would end – that dissonant facts made them double-down. It would be too painful to be wrong, and so they convinced themselves that they were right.

Smoking

Smoking is a common example of cognitive dissonance because it is widely accepted that cigarettes can cause lung cancer, and smokers must reconcile their habit with the desire to live long and healthy lives. In terms of the cognitive dissonance theory, the desire to live a long life is dissonant with the activity of doing something that is likely to shorten one's life.

Smokers may alter their belief about the dangers of smoking by telling themselves that they "know a 70-year-old man who has smoked since he was a teenager and is still very healthy". Or a person could believe that smoking keeps one from gaining weight, which would also be unhealthy.

Other smokers just don't read anything about the dangers of smoking, so that they don't have to think about the negative consequences of their decision to smoke. That is one of the reasons that some governments require warning labels to be printed on all cigarette packaging.

Dissonance Reduction

People want to harmony between their expectations and reality. When cognitive dissonance appears, they engage in a process termed "dissonance reduction", which can be achieved in one of three ways:

- (1) lowering the importance of one of the factors raising the concern,

- (2) adding or inventing new facts, or

- (3) changing one of the dissonant factors.

This bias sheds light on otherwise puzzling, irrational, and even destructive behavior.

Followers of William Branham's message

Cognitive dissonance has been repeatedly seen in the followers of William Branham when presented with the evidence available on this website.

Five conditions met in followers of William Branham

Festinger stated that five conditions must be present if someone is to become a more fervent believer after a failure or disconfirmation. With respect to followers of William Branham, these have been identified as follows:

- The belief that William Branham is a prophet of God is held with deep conviction and, in most cases, creates a significant change in the life style of message believers.

- Following the "message" generally involves a significant personal commitment. This will also often involve significant confrontation with family members and close friends and a deep separation from these people. For women, it generally involves a complete change in dress and hairstyle that is obvious to friends and relatives.

- The beliefs held by message believers about William Branham are very specific with respect to his prophecies and general credibility. Sufficient evidence to unequivocally refute belief in William Branham has been presented on this website.

- It has been shown conclusively that all of William Branham's prophecies were "after the fact".

- It has been proved that the few "before the fact" prophecies that he made all failed.

- Many specific statements of William Branham have been shown to be lies.

- Undeniable evidence has been presented on this website that William Branham was not a prophet and this has been recognized as such by many ministers and individual believers in the message. It has resulted in many "believers" leaving the message.

- The individual believer has a social support network that is derived from the message church that they attend.

Specific examples in "message believers"

Cognitive dissonance has been created in a number of people that have viewed the information on this website and we have been able to view the impact through email correspondence with message believers and interactions on our Facebook discussion page. Followers of William Branham's message are rarely prepared to actually put their beliefs under the microscope and actually examine them in the light of independent, objective analysis.

If the dissonance is not reduced by changing one's belief in the message, then message believers restore consonance through misperception (allowing the truth to be distorted by one's own perceptions); rejection or refutation of the information that we are presenting; seeking support from other message believers in rejecting the information presented on this website; and attempting to persuade others that the information that is contained on this website is wrong.

Examples include:

- The Municipal Bridge Vision

- The fact that this vision took place when William Branham was a child is grounds for it being ignored, as he could have made a mistake. This ignores the fact that he said that it was fulfilled, and it is the fulfillment that creates the problem, i.e. it never happened.

- This happened a long time ago and therefore it is likely that the deaths of the workers simply went unreported. This ignores the fact that the wives, parents and children of a group of 16 men that perished in a construction accident would not permit their memory to be forgotten. For that reason, the deaths in the construction of the Big Four Bridge are still remembered. A death of one person might be forgotten but not 16 men.

- African Vision - To avoid this issue, people will say that William Branham was referring to India, not Africa, even though he specifically mentions Durban, South Africa in the vision. Or another method of avoiding the implication of this failed vision is to state that well over 300,000 people have heard the tapes in South Africa thereby fulfilling the vision, although this again is an irrelevant rationalization.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt - To deal with this failed prophecy, followers of William Branham search out explanations that are rooted in conspiracy theory.

Footnotes

- ↑ Festinger, Leon; Henry W. Riecken, Stanley Schachter (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 1-59147-727-1.

- ↑ David G. Benner and Peter C. Hill, eds., Baker Encyclopedia of Psychology & Counseling, Baker Reference Library (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999), 220.

- ↑ Festinger, Leon; Henry W. Riecken, Stanley Schachter (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 1-59147-727-1.

- ↑ David G. Benner and Peter C. Hill, eds., Baker Encyclopedia of Psychology & Counseling, Baker Reference Library (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999), 220.