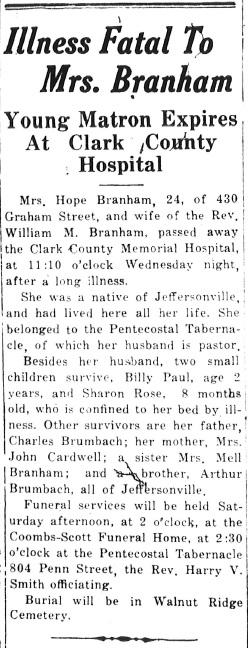

The death of Hope Branham

Hope Branham (nee Brumbach) died on July 21, 1937 as a result of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Most message followers believe that her death was a direct result of the Ohio River flood of 1937, but is this factual?

It is also interesting to note that she attended the "Pentecostal Tabernacle, of which her husband is the pastor."

The story as told by William Branham

William Branham stated (see the quotes below) that his wife contracted pneumonia just before Christmas, 1936 and that he did not find out that she had TB until weeks after the Ohio River flood of 1937, which took place in January and early February of 1937. He also stated that she was twenty years old when she died. In another place, he said she was twenty-one years old when she died.

He also stated that he found out that his daughter, Sharon Rose, was sick after his wife died.

The facts

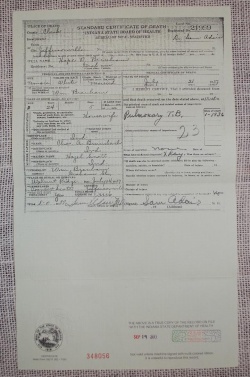

According to the death certificate signed by Dr. Sam Adair, Hope Branham died on July 21, 1937. She had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in January, 1936 and the diagnosis had been confirmed by X-Ray. The death certificate also states that she was twenty-four years old when she died (her date of death was 5 days after her 24th birthday).

Hope Branham appears to have been diagnosed with TB about the time that she became pregnant with her daughter. This is likely why the child died an early death.

The death certificate of Sharon Branham states that she died on July 26, 1937 at the age of 8 months, 28 days. She was diagnosed with tubercular meningitis on July 20, 1937, the day before her mother died. Her death certificate also states that she also had pulmonary tuberculosis at the time of her death.

Conclusion

William Branham tells a heart-wrenching story of the early death of his wife and daughter. That much is true.

But his tale of not finding out about his wife's illness until after the flood, appears to have been a complete fabrication. The doctor diagnosed Hope Branham with TB over a year and a half before she died. And how do you get your wife's age wrong by 4 years?

Furthermore, the death certificate of his daughter states that she was diagnosed with tubercular meningitis the day before her mother died, and not the day after.

That significant portions of this story is a fabrication is further confirmed by the details he relates about Hope's nurse.

The question we can't answer is why William Branham made up portions of this story as sermon material. Was it to make it more dramatic for the audience? We can never know for sure...

Quotes of William Branham

But she taken pneumonia when she went to get the children a Christmas present. And the doctor said she'll have to lay right here, Billy, 'cause she's—probably will die if—if she ever moves. But her mother come up and said she was going to move her down to her house. And Dr. Adair said, "She'll have to get another doctor, 'cause I wouldn't do it, Billy," wouldn't permit it.

...And the flood broke through, and then all of us was put on the rescue to—to work with the flood. We rushed her out to the government hospital where they temporary placed the hospital. The dikes was breaking through; the city was washing away. I'll never forget those nights. I remember they called me. Both babies was sick with pneumonia, and she was laying sick with pneumonia, out in the hospital there with a fever a hundred and five and both babies sick.

...So they said, "You looking for her?" And I said… Said, "My girlfriend is at Columbus, Indiana, and your wife is laying by her side dying with…?… tuberculosis." I said, "No, it can't be." Said, "Yes, she is."

...He said, "Well, I'm going to tell you," said, "you better get ready for this." Said, "Your wife is going to die," said, "she's got TB." And I said, "That's galloping consumption." And said, "She won't last for just a little while."[1]

Just right after that, the 1937 flood come on. And when it did, the… I was—got a job then. I went to working for the conservation. And I was patrolling out in the… So when I—the floods begin to come up and you remember hearing it here.

...And when I come in that afternoon, she was laying on the floor, fainted. And I called our family doctor, Doctor Adair. And he—he came up there, and he said, "Well, Bill, she's got pneumonia." So he said, "You have to stay up all night…?… nights." And during that time… Before that, a little girl baby, little Sharon Rose (Bless her little heart. She's in heaven too today.), she had been born into our home, just the sweetest little thing you ever seen, just a few months old.

And so then I remember that Doctor Adair told me, he'd say, "Have to stay up late, Billy, keep the children out of the room here." And said, "Stay up and—and—and give a lot of fluid that night." And I did. And the next morning her mother wanted to take her down at the house. And she didn't care too much about Doctor Adair, and taken her out and throwed her into the—the tubercular. So then, I remember the flood coming on; they rushed her out to the government depot, out there for the hospital. And—and, oh, that part of the night, it raining, twisting, blowing; and how brother, sister…?… now. Always mind God. No matter what it is, God says for you to do. And I tell you, today, that God in heaven, Who looks down upon me standing in this platform, will forgive me. I know that many thousands of souls that I'll have to answer for at that day, for listening to somebody else instead of God. That's true. Now, I remember out there that night. They taken her out to the government barracks where, used it for people who are in hospitals. And the floods were on.

And I was down trying to patrol. I slip out to see her. And she was sick, and both babies had taken pneumonia. And they were laying there sick and… And I'd worked back. They was calling me everywhere in patrol car I was in… I went downtown. And—and I was coming up the street along about eleven o'clock.

...I slipped out to the ho—or the government hospital to find out how my wife was. I was going to talk to her about it. And I went out there, and they was just laying in little old army cots. And when I got there, it was all covered over with water. Where were they at? Then I started screaming to the top… And I got excited then.

Major Weekly, a friend of mine there at the government, he walked up to me. He said, "Reverend Branham?" I said, "Yes, sir." He said, "I don't think your wife is gone." Said, "I think they got everybody out of there." Said, "I think they went to Charlestown, a city about twelve, fourteen miles above here." Said, "I think they went out in a cattle car." Her with pneumonia and it sleeting and blowing like that. Two sick babies and them with pneumonia, one of them just eight months old. I thought, "Oh mercy, they was on a cattle car." Then I jumped in my truck and run out there towards—to get the road to go to Charlestown. There's about six miles of water where the Lancassange Creek had come through like this to get back. I run down and got my speed boat, and I'd tried my best to get through them waves. I'd hit like this and go plumb back around like that, and I tried to duck the waves.

..."Did any of them in the hospital get drowned, you know?" He said, "No, I don't think there was." He said, "I think they all escaped." And said, "Reverend Branham, I think your wife was on a box car, and they took her out to Charlestown when that boat went up." 90 Well, I run down to my car and got my speedboat, and come back up and put it on the back of my truck. Run up and started to cross. I set up there to…?… was back to it, and about six miles of water just waves through there. Some of them said, "That train?" Said "It washed off the trestles right up there." Oh, my.

There it was again. I tell you, brother, back down in behind this heart, there is sorrows that you know nothing about… Then I put that boat in the water, and I tried hour after hour to pierce that current. And I couldn't do it. And then the water cut me off, and there I was marooned out there for about seven days I set out there. I had plenty of time to think things over. When the waters got down…?… I had two choices. I walked up there…?… [Blank.spot.on.tape—Ed.]

...I met a man. He said, "I know who you're looking for, Billy." It was a friend of mine. Said, "You're looking for Hope, aren't you." And I said, "Jim, you know about her?" Said… I mean at… not at Kokomo, it's Seymour, Indiana. He said, "She's laying up there in the Baptist church at Seymour, Indiana, dying with tuberculosis, laying by the side of my wife." And I… or "my girlfriend."

And I said, "Dying with TB?" Said, "Yes, Bill." Said, "I hate to tell you, but you wouldn't know her." I said, "Is the babies alive?" Said, "I don't know nothing about the babies." Oh, my. I said, "Oh, can we get there?" Said, "I got a secret road." Said, "I can take you." And we got in there late that night, in the—the basketball arena where the Baptist church was fixed up for the—the refugees to come in. And they said she was down there. And I run through there screaming top of my voice, "Hope! Hope, honey! Where are you? Where are you?" And I looked.

Oh, I will never forget that. Back over there on this old government cot, I seen a little bony hand raise up. That was my darling. I run to her real quick. I fell down at her. Those dark eyes was sunk way back in her head. She'd falling lots of weight. I said, "Sweetheart?" She said, "I look awful, don't I?" I said, "No, honey. Is the babies all right?" "Yes," she said. "Mother has the babies." Said, "Billy's been awfully sick; Sharon's a little better." And she said, "I'm awfully sick." I started crying, I said, "God, don't—don't take her from me. Please don't, Lord."

I felt somebody touch me on the back. It was a doctor. "You're Reverend Branham?" And I said, "Yes, sir." "Come here just a minute." Said, "Aren't you a friend of Sam Adair?" And I said, "Yes, sir, I am." He said, "I hate to tell you this, Reverend Branham, but your wife's a dying." Said, "Your wife's got tubercular. Sam told me to tell you just to make her comfortable, and not to be excited around her." I said, "She dying, doctor?" I said, "She can't, doctor. That's all. She can't do it." I said, "I love her with all my heart, and I'm a Christian." And I said, "I just—I just know she ain't going to die. I just can't think of the thoughts to think that she'd be taken away from me here, and with these two little babies, how could I stand it?" He said, "Well, I hate to tell you, but," said, "there's nothing can be done as far as I know."

I went back to her, trying to brace myself up and talk to her. A few days we took her home. She just kept getting worse and worse and worse. Went to Louisville, and they had specialists and everything. Took her out to the hospital. Doctor Miller from the sanatorium come down and looked. He called me out to one side, said, "Reverend Branham, she's going to die." Said, "There ain't nothing can be done for her." Said, "She's—she's going to die." I said, "Doctor Miller, honest, isn't there something I can do? Could I take her to Arizona? Could I do something for her?" Said, "It's too late now, Billy." Said, "That—that's a… That's galloping tubercular." Said, "It—it kills them right away." Said, "Her family's had it back behind there," which I knew later that they—they did. And said, "She's just broke with it, and it's got such a hold on her." Said he'd give her pneumothorax treatments and everything. And said…

...And I'd hold her hand when they were boring that hole in her side to collapse them lungs. If I had it to go over, it wouldn't be done. And she'd hold my hand there, bless her heart. I'd have to almost pull her hand off of mine from suffering, holding where they'd bore that hole in there and collapse the lungs on the side. And that was tubercular traveling right on up like that. I knew she was going, and I was doing all that I could do. And I'd work at night. I remember, I was out, and I heard a patrol sign come through. It said, "Calling William Branham. Come to the hospital immediately, wife dying." 98 I never will forget; I took off my hat. Setting in the truck, I held up my hands, and I said, "O Jesus, please don't let her go. Let me talk to her once more before she goes. Please do save her." I was about twenty miles away from home. I turned on lights and everything. I went down the road real swift, stopped in front of the hospital, and throwed off the gun belt, and into the place I went real quick.

I started walking down through the Clark County Memorial Hospital. As I started down through there, I looked, and I seen poor little Doctor Adair come walking down through there with his head down. God bless that man. And he—he looked at me like that when he seen me. He throwed his hands up like that and started crying and run in the halls. And I run up to him, put my arm around him, I said, "Sam, is it?" And he said, "Billy, I'm—I'm afraid she's gone now." I said, "Come, go with me, Doc. Let's go in." He said, "Bill, please don't ask me to do that." Said, "Oh Bill, I love you." He put his arms around me. Said, "I love you, Billy." He said, "We've been bosom friends." He said, "I can't go in and look at Hope again." Said, "That's like my sister laying there." Said, "She's baked me pies and everything." Said, "How—how could I go in and see her going like that." Said, "Come here, nurse." I said, "No. No, let—let me go myself."

...They done had the sheet pulled up over her face. I pulled that sheet down and looked. She was real thin, and she was drawed up like this. I put my hands on her; perspiration's real sticky; her face was cold. I shook her. I said, "Hope, Sweetheart? Please speak to me once more." I said, "God, have mercy." I said, "Never again will I think them people are trash. I'll make my stand." During that time, we'd both received the Holy Ghost. So I said, "Please, will You, Lord?" I shook her. I said, "Oh, please speak to me once more." And I—I shook her again like that. Those great big dark eyes looked up at me. She said, "Come near." And I got down real close to where she was. She said, "Oh, why did you call me, honey?" I said, "Call you?" I said, "Sweetheart, I thought you were gone." She said, "Oh, Bill…" About that time the nurse run in, said, "Reverend Branham, here." Said… "You had that little medicine?" I said, "No."

She called the nurse, Miss Cook. She said, "Come here." She said, "Set down just a minute. I've just got a few minutes left." And she was Hope's friend. And she was biting her lip. She said, "When you get married, I hope you get a husband like mine." And that… You know how it made me feel. She said, "He's been good to me, and we've loved each other the way we have." And said, "I hope you get a husband like mine." I—I turned my head; I couldn't stand it…?… walked out of the room. I walked over to her I said, "Sweetheart, you're not going to leave me, are you?"

...She threw her hands up like that. And I kissed her good-bye. She went to be with God. That's my date with…?… I'm living as true as I know how to keep it. Someday I'll be there by God's grace. When I returned home, oh, how I felt. I just couldn't hardly stand it, how they'd—they taken her down to the undertaker morgue and then they embalmed her body and laid her out. I was laying there that night; I happened to look. Somebody knocked at the door, Mr. Broy come up, he said, "Billy," said, "I hate to tell you the bad news." I said, "Brother Frank, I know she's down there in the morgue." I said… He said, "That's not all of it." Said, "Your baby's dying too." I said, "My what? Sharon's dying?" Said, "Sharon's a dying." Said, "They just took her to the hospital, and Doctor Adair said she can't live but just a little bit longer."[2]

About few weeks after that, things begin to happen. The flood come on later from that. And the first thing you know, wife got sick, Billy got sick; during that wrong. Right after that, the little girl… Just eleven months difference between Billy and his little—his little sister, which was Sharon Rose. I wanted to name her a Bible name. So I couldn't call her the Rose of Sharon, so I called her Sharon Rose; and I—I named her that. She was a darling lovely little thing. And the first thing you know, the flood came up. She was laying there with pneumonia. And our doctor, Dr. Sam Adair came. And he's a brother to me. He looked at her, he said, "Bill, she's seriously ill." Said, "Don't you go to bed." Right at Christmas time. He said, "Don't you go to bed tonight. You give her orange juice all night long. Make her drink at least two gallons tonight to break that fever. She's got a fever of hundred and five," and said, "You must break that fever right away."[3]

A great flood hit the country and washed away the homes. My wife was in the hospital. And I was out on a rescue with my boat. And one night out in the water, my boat got in the current, and was going over a big falls. I couldn't get the motor started, and I raised up my hands, and I said, "Oh, God, don't let me drown. I am not worthy to live, but think of my wife and baby." And I tried again, and it wouldn't start, and I cried again to God. And then, just before going over the falls, the motor started, and I got to the land.

And then I tried to find my wife. And when I got to the hospital, it was covered over with water. The dike had broke, and all the waters gushed in. Where was my wife and baby? I begin to find people [Blank.spot.on.tape—Ed.]… see if there was anyone drowned, but they got away on a train. And here I was setting on an island by myself. God give me a chance so—whether to call people trash or not. I said, "God, I know I've mis—I've misbehaved myself. Don't let my wife be killed."

Weeks later when the waters went down, I found her almost dead. TB had hit her; my two children were sick. And I loved my wife. And I run through the building trying to find her. And I screamed for her. And I seen her laying on a cot in a refugee's camp. And her eyes were way back. And she raised her hands; it was real bony. And I started weeping. And she said, "Oh Bill, I—I—I'm sorry I look like this."

...And then she opened her eyes. Oh, I shall never forget it. And when I—she looked at me, she tried to raise her—raise her hands for me. And I got down close to her. She said, "Oh, Billy, I love you so much. Billy, I'm going away, and I want you to be a good boy." She was twenty-one. She was twenty-one. I was twenty-three.[4]

My mind goes back tonight, many miles away on a hillside tonight, where marks the very place of my beloved wife, that left me at—when she was twenty years old. I laid my darling little eight months old Sharon on her arm, as I buried them together.[5]

Footnotes