William Branham and the Trinity Doctrine: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

|The Trinity is an explanation of the [[The Godhead]] that has historically been accepted by most of the world's Christian churches. The word "Trinity" was first used circa. A.D. 200 by Tertullian, a Latin theologian from Carthage who later abandoned Christianity for Montanism. | |The Trinity is an explanation of the [[The Godhead]] that has historically been accepted by most of the world's Christian churches. The word "Trinity" was first used circa. A.D. 200 by Tertullian, a Latin theologian from Carthage who later abandoned Christianity for Montanism. | ||

=William Branham's Critique of the Trinity= | |||

William Branham's arguments against the doctrine of the Trinity are referred to as '''"straw man"''' arguments: | William Branham's arguments against the doctrine of the Trinity are referred to as '''"straw man"''' arguments: | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

It is important to notice that William Branham's critique of the doctrine of the Trinity is not backed up by a lot of scripture. So first, he misrepresented the doctrine of the Trinity (no Trinitarian believes in three Gods), and then critiqued his own misrepresentation of the Trinity. | It is important to notice that William Branham's critique of the doctrine of the Trinity is not backed up by a lot of scripture. So first, he misrepresented the doctrine of the Trinity (no Trinitarian believes in three Gods), and then critiqued his own misrepresentation of the Trinity. | ||

=The Historic Doctrine of the Trinity= | |||

So that we are all on the same page, a basic definition of the Trinity is necessary: | So that we are all on the same page, a basic definition of the Trinity is necessary: | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Commonly referred to as "One God in Three Persons", the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are identified as distinct and co-eternal "persons" or "hypostases," who share a single Divine essence, being, or nature. | Commonly referred to as "One God in Three Persons", the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are identified as distinct and co-eternal "persons" or "hypostases," who share a single Divine essence, being, or nature. | ||

==Three Gods?== | |||

William Branham's primary argument against the Trinity was a logical fallacy referred to as "a straw man". | |||

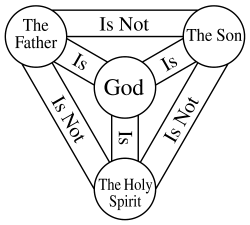

[[Image:3people.jpg|thumb|150px|A misleading impression of the Trinity (by Fridolin Leiber) as "person" does not mean "individual". Don't try to paint God (or take pictures of lights and claim it's God) and think you're going to get it right. ]] | [[Image:3people.jpg|thumb|150px|A misleading impression of the Trinity (by Fridolin Leiber) as "person" does not mean "individual". Don't try to paint God (or take pictures of lights and claim it's God) and think you're going to get it right. ]] | ||

:''A man come to me the other night to show me where I was wrong, or to talking about the trinity. I got thousands of good trinity friends. They're in that Babylon. I got a lot of Oneness friends in that Babylon, too. See? But what happened? He said, "It's terminology, Brother Branham. You believe in the trinity?" | :''A man come to me the other night to show me where I was wrong, or to talking about the trinity. I got thousands of good trinity friends. They're in that Babylon. I got a lot of Oneness friends in that Babylon, too. See? But what happened? He said, "It's terminology, Brother Branham. You believe in the trinity?" | ||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

However, his position disagrees with all of the great spiritual men of the church that preceded him, and he chose to ignore them as well: | However, his position disagrees with all of the great spiritual men of the church that preceded him, and he chose to ignore them as well: | ||

==A Defense of the Trinity by historical Christian figures== | |||

The following are a few well known Christian figures through history that have defended the Trinity doctrine in very clear terms: | The following are a few well known Christian figures through history that have defended the Trinity doctrine in very clear terms: | ||

===Martin Luther=== | |||

:''The evangelist clearly differentiates between the Word and the Person of the Father. He stresses the fact that the Word was a Person distinct from the Person of the Father, with whom He was. He was entirely separate from the Father. John wishes to say: “The Word, who was in the beginning, was not alone but was with God.” Just as if I should say: “He was with me; he sits at my table; he is my companion.” This would imply that I am speaking of another, that there are two of us; I alone do not constitute a companion. Thus we read here: “The Word was with God.” | :''The evangelist clearly differentiates between the Word and the Person of the Father. He stresses the fact that the Word was a Person distinct from the Person of the Father, with whom He was. He was entirely separate from the Father. John wishes to say: “The Word, who was in the beginning, was not alone but was with God.” Just as if I should say: “He was with me; he sits at my table; he is my companion.” This would imply that I am speaking of another, that there are two of us; I alone do not constitute a companion. Thus we read here: “The Word was with God.” | ||

| Line 57: | Line 58: | ||

:''There are two distinct Persons; and still there is one single, eternal, natural God. The Holy Spirit is likewise a Person, apart from the Father and the Son; and at the same time the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one divine essence and remain one God, three Persons in the one divine essence. Therefore the Holy Trinity must be spoken of correctly and accurately: The Word, which is the Son, and God the Father are two Persons but nevertheless one God; and the Holy Spirit is another Person in the Godhead, as we shall see later.<ref>Martin Luther, vol. 22, Luther's Works, Vol. 22: Sermons on the Gospel of St. John: Chapters 1-4, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald and Helmut T. Lehmann, 15-16 (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999).</ref> | :''There are two distinct Persons; and still there is one single, eternal, natural God. The Holy Spirit is likewise a Person, apart from the Father and the Son; and at the same time the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one divine essence and remain one God, three Persons in the one divine essence. Therefore the Holy Trinity must be spoken of correctly and accurately: The Word, which is the Son, and God the Father are two Persons but nevertheless one God; and the Holy Spirit is another Person in the Godhead, as we shall see later.<ref>Martin Luther, vol. 22, Luther's Works, Vol. 22: Sermons on the Gospel of St. John: Chapters 1-4, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald and Helmut T. Lehmann, 15-16 (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999).</ref> | ||

===John Calvin=== | |||

:''Sabellius says that the Father, Son, and Spirit, indicate some distinction in God. Say, they are three, and he will bawl out that you are making three Gods. Say, that there is a Trinity of Persons in one Divine essence, you will only express in one word what the Scriptures say, and stop his empty prattle. Should any be so superstitiously precise as not to tolerate these terms, still do their worst, they will not be able to deny that when one is spoken of, a unity of substance must be understood, and when three in one essence, the persons in this Trinity are denoted. When this is confessed without equivocations we dwell not on words. But I was long ago made aware, and, indeed, on more than one occasion, that those who contend pertinaciously about words are tainted with some hidden poison; and, therefore, that it is more expedient to provoke them purposely, than to court their favour by speaking obscurely. | :''Sabellius says that the Father, Son, and Spirit, indicate some distinction in God. Say, they are three, and he will bawl out that you are making three Gods. Say, that there is a Trinity of Persons in one Divine essence, you will only express in one word what the Scriptures say, and stop his empty prattle. Should any be so superstitiously precise as not to tolerate these terms, still do their worst, they will not be able to deny that when one is spoken of, a unity of substance must be understood, and when three in one essence, the persons in this Trinity are denoted. When this is confessed without equivocations we dwell not on words. But I was long ago made aware, and, indeed, on more than one occasion, that those who contend pertinaciously about words are tainted with some hidden poison; and, therefore, that it is more expedient to provoke them purposely, than to court their favour by speaking obscurely. | ||

:''For it is absurd to imagine that our doctrine gives any ground for alleging that we establish a quaternion of gods. They falsely and calumniously ascribe to us the figment of their own brain, as if we virtually held that three persons emanate from one essence, whereas it is plain, from our writings, that we do not disjoin the persons from the essence, but interpose a distinction between the persons residing in it. If the persons were separated from the essence, there might be some plausibility in their argument; as in this way there would be a trinity of Gods, not of persons comprehended in one God. This affords an answer to their futile question—whether or not the essence concurs in forming the Trinity; as if we imagined that three Gods were derived from it. Their objection, that there would thus be a Trinity without a God, originates in the same absurdity. Although the essence does not contribute to the distinction, as if it were a part or member, the persons are not without it, or external to it; for the Father, if he were not God, could not be the Father; nor could the Son possibly be Son unless he were God. We say, then, that the Godhead is absolutely of itself. And hence also we hold that the Son, regarded as God, and without reference to person, is also of himself; though we also say that, regarded as Son, he is of the Father. Thus his essence is without beginning, while his person has its beginning in God.<ref>John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 1997).</ref> | :''For it is absurd to imagine that our doctrine gives any ground for alleging that we establish a quaternion of gods. They falsely and calumniously ascribe to us the figment of their own brain, as if we virtually held that three persons emanate from one essence, whereas it is plain, from our writings, that we do not disjoin the persons from the essence, but interpose a distinction between the persons residing in it. If the persons were separated from the essence, there might be some plausibility in their argument; as in this way there would be a trinity of Gods, not of persons comprehended in one God. This affords an answer to their futile question—whether or not the essence concurs in forming the Trinity; as if we imagined that three Gods were derived from it. Their objection, that there would thus be a Trinity without a God, originates in the same absurdity. Although the essence does not contribute to the distinction, as if it were a part or member, the persons are not without it, or external to it; for the Father, if he were not God, could not be the Father; nor could the Son possibly be Son unless he were God. We say, then, that the Godhead is absolutely of itself. And hence also we hold that the Son, regarded as God, and without reference to person, is also of himself; though we also say that, regarded as Son, he is of the Father. Thus his essence is without beginning, while his person has its beginning in God.<ref>John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 1997).</ref> | ||

===John & Charles Wesley=== | |||

:''In the three Divine Persons we acknowledge a distinction established upon Scripture authority; but, holding the unity of substance in the Godhead, we protest against tritheism, or the notion of three Gods, and confine our worship to the one Supreme.<ref>Charles Wesley, A Short Commentary on the Church Catechism, 16-17 (London: S. Low, 1836).</ref> | :''In the three Divine Persons we acknowledge a distinction established upon Scripture authority; but, holding the unity of substance in the Godhead, we protest against tritheism, or the notion of three Gods, and confine our worship to the one Supreme.<ref>Charles Wesley, A Short Commentary on the Church Catechism, 16-17 (London: S. Low, 1836).</ref> | ||

:''To God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, who yet are not three Gods, but One, revered by all His host... <ref>John Wesley and Charles Wesley, The Poetical Works of John and Charles Wesley, Volume 2, ed. G. Osborn, 21 (London: Wesleyan-Methodist Conference Office, 1869).</ref> | :''To God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, who yet are not three Gods, but One, revered by all His host... <ref>John Wesley and Charles Wesley, The Poetical Works of John and Charles Wesley, Volume 2, ed. G. Osborn, 21 (London: Wesleyan-Methodist Conference Office, 1869).</ref> | ||

===Charles Spurgeon=== | |||

:''I no more believe in three Gods than I believe in thirty gods. There is but one God to me, and therefore I am in that sense a Unitarian, and Socinians have no right to the name merely because they deny the Godhead of our Lord Jesus. We believe Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be one God; but Jesus Christ is God, and whosoever casts that truth away casts away eternal life. How can he enter into heaven if he does not know Christ as the everlasting Son of the Father? He must be God, since he has promised to be in ten thousand places at one time, and no mere man could do that.<ref>C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, Vol. XXX, 46 (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1884).</ref> | :''I no more believe in three Gods than I believe in thirty gods. There is but one God to me, and therefore I am in that sense a Unitarian, and Socinians have no right to the name merely because they deny the Godhead of our Lord Jesus. We believe Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be one God; but Jesus Christ is God, and whosoever casts that truth away casts away eternal life. How can he enter into heaven if he does not know Christ as the everlasting Son of the Father? He must be God, since he has promised to be in ten thousand places at one time, and no mere man could do that.<ref>C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, Vol. XXX, 46 (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1884).</ref> | ||

===C.S. Lewis=== | |||

:''You know that in space you can move in three ways – to left or right, backwards or forwards, up or down. Every direction is either one of these three or a compromise between them. They are called the three Dimensions. | :''You know that in space you can move in three ways – to left or right, backwards or forwards, up or down. Every direction is either one of these three or a compromise between them. They are called the three Dimensions. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 84: | ||

:''In God’s dimension, so to speak, you find a being who is three Persons while remaining one Being, just as a cube is six squares while remaining one cube. Of course we cannot fully conceive a Being like that: just as, if we were so made that we perceived only two dimensions in space we could never properly imagine a cube. But we can get a sort of faint notion of it. And when we do, we are then, for the first time in our lives, getting some positive idea, however faint, of something super-personal – something more than a person. It is something we could never have guessed, and yet, once we have been told, one almost feels one ought to have been able to guess it because it fits in so well with all the things we know already.<ref>C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. 161-162</ref> | :''In God’s dimension, so to speak, you find a being who is three Persons while remaining one Being, just as a cube is six squares while remaining one cube. Of course we cannot fully conceive a Being like that: just as, if we were so made that we perceived only two dimensions in space we could never properly imagine a cube. But we can get a sort of faint notion of it. And when we do, we are then, for the first time in our lives, getting some positive idea, however faint, of something super-personal – something more than a person. It is something we could never have guessed, and yet, once we have been told, one almost feels one ought to have been able to guess it because it fits in so well with all the things we know already.<ref>C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. 161-162</ref> | ||

=The Limitations of the Doctrine= | |||

The doctrine of the Trinity is the result of continuous exploration by theologians of scripture and philosophy, argued in debate and treatises. However, William Branham felt that he could reject almost 2000 years of thought and study out of hand: | The doctrine of the Trinity is the result of continuous exploration by theologians of scripture and philosophy, argued in debate and treatises. However, William Branham felt that he could reject almost 2000 years of thought and study out of hand: | ||

| Line 97: | Line 98: | ||

:''Perhaps the very best one is that of St. Patrick, who, when preaching to the Irish, and wishing to explain this matter, plucked a shamrock and showed them its three leaves all in one—three, yet one. Yet there are flaws and faults even in that illustration. It does not meet the case. It is a doctrine to be emphatically asserted as it is expounded in that Athanasian Creed; the soundness of whose teaching I do not question, for I believe it all, though I shrink with horror from the abominable anathema which assert that a man who hesitates to endorse it will “without doubt perish everlastingly.” It is a matter to be reverently accepted as it stands in the Word of God, and to be faithfully studied as it has been understood by the most scrupulous and intelligent Christians of succeeding generations. | :''Perhaps the very best one is that of St. Patrick, who, when preaching to the Irish, and wishing to explain this matter, plucked a shamrock and showed them its three leaves all in one—three, yet one. Yet there are flaws and faults even in that illustration. It does not meet the case. It is a doctrine to be emphatically asserted as it is expounded in that Athanasian Creed; the soundness of whose teaching I do not question, for I believe it all, though I shrink with horror from the abominable anathema which assert that a man who hesitates to endorse it will “without doubt perish everlastingly.” It is a matter to be reverently accepted as it stands in the Word of God, and to be faithfully studied as it has been understood by the most scrupulous and intelligent Christians of succeeding generations. | ||

:''We are not to think of the Father as though anything could detract from the homage due to him as originally and essentially divine, nor of the only begotten Son of the Father as though he were not “God over all, blessed for ever,” nor of the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and the Son, as though he had not all the attributes of Deity. We must abide by this, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord thy God is one Jehovah”; but we must still hold to it that in three Persons he is to be worshipped, though he be but one in his essence.<ref>C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, Vol. LXII, 315-16 (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1916).</ref> | :''We are not to think of the Father as though anything could detract from the homage due to him as originally and essentially divine, nor of the only begotten Son of the Father as though he were not “God over all, blessed for ever,” nor of the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and the Son, as though he had not all the attributes of Deity. We must abide by this, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord thy God is one Jehovah”; but we must still hold to it that in three Persons he is to be worshipped, though he be but one in his essence.<ref>C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, Vol. LXII, 315-16 (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1916).</ref> | ||

=Quotes of William Branham= | |||

''But here, remember, there was a Gethsemane conference come one time, '''when God and His Son had to get together'''. After all, there was no one else could die for the sins of the world. There was nobody worthy to die, no man.<ref>William Marrion Branham, 63-0608, Sermon: Conferences</ref> | |||

{{Bottom of Page}} | {{Bottom of Page}} | ||

Revision as of 23:47, 22 July 2015

This article is one in a series of studies on William Branham and the Trinity - you are currently on the topic that is in bold:

- What did William Branham believe about the Godhead?

- William Branham and the Trinity Doctrine

- The Historic Doctrine of the Trinity

- Did William Branham Teach Oneness?

- William Branham and Arianism

- Did William Branham teach Nestorianism?

- Bible Study on the Trinity

- Q&A on the Godhead - Answers to emails we have received

- Christians that God required to believe the Satanic Trinity doctrine

- Other articles on the Godhead

- Giants of the faith who believed the doctrine of the Trinity

The Trinity is an explanation of the The Godhead that has historically been accepted by most of the world's Christian churches. The word "Trinity" was first used circa. A.D. 200 by Tertullian, a Latin theologian from Carthage who later abandoned Christianity for Montanism.

William Branham's Critique of the TrinityWilliam Branham's arguments against the doctrine of the Trinity are referred to as "straw man" arguments:

A straw man is a common type of argument and is an informal fallacy based on the misrepresentation of an opponent's argument. To be successful, a straw man argument requires that the audience be ignorant or uninformed of the original argument. The typical "attacking a straw man" argument creates the illusion of having completely refuted or defeated an opponent's proposition by replacing it with a different proposition (i.e., "stand up the straw man") and then to refute or defeat that false argument ("knock down the straw man") instead of what your opponent actually believes. This technique has been used throughout history in debate, particularly in arguments about highly charged emotional issues where the defeat of the "enemy" is more valued than critical thinking or understanding both sides of the issue. It is important to notice that William Branham's critique of the doctrine of the Trinity is not backed up by a lot of scripture. So first, he misrepresented the doctrine of the Trinity (no Trinitarian believes in three Gods), and then critiqued his own misrepresentation of the Trinity. The Historic Doctrine of the TrinitySo that we are all on the same page, a basic definition of the Trinity is necessary:

Commonly referred to as "One God in Three Persons", the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are identified as distinct and co-eternal "persons" or "hypostases," who share a single Divine essence, being, or nature. Three Gods?William Branham's primary argument against the Trinity was a logical fallacy referred to as "a straw man".

William Branham clearly understood that the doctrine of the Trinity did not teach that there were three gods but chose to ignore the reasons for this position. Instead of focusing on the reasons that the church had adopted this position for millienia, he chose to reject it simply on the basis that it didn't make sense to him. However, his position disagrees with all of the great spiritual men of the church that preceded him, and he chose to ignore them as well: A Defense of the Trinity by historical Christian figuresThe following are a few well known Christian figures through history that have defended the Trinity doctrine in very clear terms: Martin Luther

John Calvin

John & Charles Wesley

Charles Spurgeon

C.S. Lewis

The Limitations of the DoctrineThe doctrine of the Trinity is the result of continuous exploration by theologians of scripture and philosophy, argued in debate and treatises. However, William Branham felt that he could reject almost 2000 years of thought and study out of hand:

However, it is important to understand that theologians believe that the doctrine of the Trinity is a very difficult issue:

Quotes of William BranhamBut here, remember, there was a Gethsemane conference come one time, when God and His Son had to get together. After all, there was no one else could die for the sins of the world. There was nobody worthy to die, no man.[15]

Footnotes

|