The Houston Photograph

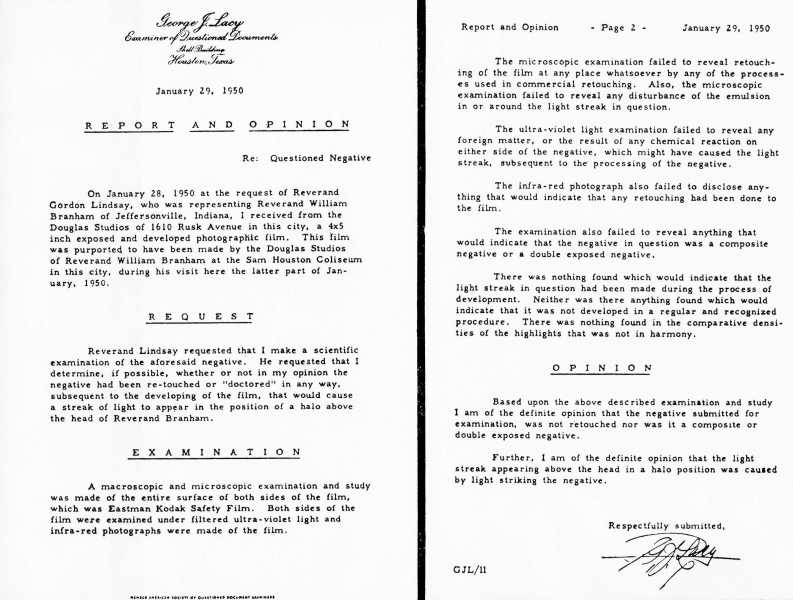

In Houston, Texas, on January 24, 1950, a strange photograph was taken by the Douglas Studios of a halo-like light above the head of Rev. William Branham. Gordon Lindsay took the negative to George J. Lacy, Examiner of Questioned Documents (who had acted as an external specialist for the FBI). George J. Lacy was asked to determine whether or not the light could have been the result of improper exposure, developing or retouching. This investigation concluded that the unusual brightness was caused by light striking the negative.

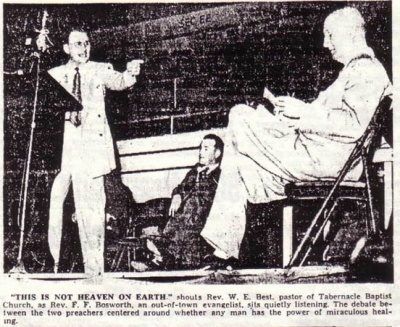

Facts surrounding the pictureIt was during the Houston campaign in 1950, that Rev. W. E. Best (representing the Houston Baptist Pastor's Conference) accused William Branham of racketeering and leading people astray. A public challenge was issued, and F.F. Bosworth accepted a challenge on the subject of "Divine Healing Through the Atonement." While Bro. Branham cautioned Brother Bosworth against being argumentative, the newspapers reported that the two ministers talked at once, and a fist-fight broke out in the audience. The meeting was given front-page publicity in the Houston newspapers. As the debate got under way, it was quite apparent that the sympathy of the vast audience was almost entirely on the side of the visiting evangelists. Large numbers of members from the same denomination as Rev. Best stood to their feet as witnesses that they believed in Divine healing and had in fact been healed. Rev. Best secured the services of Mr. James Ayers and Mr. Ted Kipperman, professional photographers from Douglas Studios in Houston, to document the evening. They were there in addition to the newpaper photographers. After taking several photos of Rev. Best, the photographer snapped a picture of William Branham, who spoke briefly just before the service closed. What William Branham said about the eveningWilliam Branham said that God would not allow a picture to be developed of Rev. Best pointing his finger at F.F. Bostorth  Click here to read a copy of the January 24th, 1950 issue of The Houston Press.

William Branham also said that it was George J. Lacy who first called it a supernatural light

ScepticismGeorge J. Lacy's report did not comment on whether the source of the light was natural (i.e. electric indoor lighting) or supernatural. While newspaper articles about the Coliseum around that time show that there were flood lights in the building (including photographs of a concert by the Beatles), George J. Lacy's report does not indicate anything about the source of the light. Some observers note that if the pillar of fire was directly over William Branham's shoulder, it would have cast light on top of his head and the pulpit. Instead, the top of his head is not lit and the light appears to be from a source beyond William Branham. These observers state that if the light was not from indoor lighting, it may have been the result of the flash from the camera reflecting off a metal pole or beam in the background. A Better Explanation?The picture on the right is from the Sam Houston Coliseum in 1969. At right is Willie Somerset (#12) of ABA's Houston Mavericks basketball team. Note the "pillar of fire" type light by the player's hand. If we zoom into the light by the players hand (see photo on left), we see something that is not that dissimilar to that of the picture of the "pillar of fire" that was photographed over William Branham's head. And this also lines up with the argument that the light passed through the lens of the camera. The Light Struck the LensIf, as George J. Lacy confirmed in his report on the photograph that light struck the negative, then it is hard to understand how no one else in the auditorium saw the light above William Branham's head. But if the light was, in fact, a bank of floodlights then light did pass through the lens and did strike the negative. The reason no one noticed the "pillar of fire" was that they all saw it for what it really was - one of the flood lights in the Sam Houston Coliseum. Report by George J. LacyAfter conferring with Rev. Branham, Gordon Lindsay arranged for the negative to be turned over to George Lacy, a forensic examiner of documents. Mr. Lacy examined the negative. After his examination, Mr. Lacy gave a certified statement indicating that it was his opinion that the negative was genuine, and had not been "doctored" or retouched or the result of a double exposure. Today, the picture sits in a filing cabinet in the U.S Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. [1]  |