The King James Version of the Bible

William Branham believed that God wrote "three Bibles": the Zodiac, the Pyramids and the written Bible that we are familiar with. But is this true?

This article is one in a series on "God's Three Bibles" - you are currently in the article that is in bold:

- William Branham and the Pyramids

- William Branham and the Zodiac

- William Branham and the Bible

- The King James Version of the Bible

While the King James Bible stands as, perhaps, the gold standard of literary significance, in some Christian circles; it holds a nearly mythological status, wherein the King James Version is perceived to possess an inherent superiority over other English translations. This is a pervasive myth, born in error and propagated in ignorance.

It is widely believed within the message, that the King James Version of the Bible is the only true “Word of God”. This belief includes the rejection of newer translations as having been “watered down”, “perverted”, or “twisted”. These are serious claims, not to be taken lightly, as the integrity of the written Bible is, obviously, of paramount importance. There are many English translations available today, so as responsible Christians, how do we know we are reading what God intended? It is expedient that we know the truth about this subject. Is the King James Version Bible the only accurate translation? If not, is it, perhaps, the most accurate? Is it somehow divinely inspired in a way that other translations are not? Or have some confused its other name, the Authorized Version to mean, as if by King Jesus, instead of King James I?

If the KJV was good enough for Paul, it's good enough for me!

First of all, it is important to understand that there is no “original” English Bible. All English versions of the New Testament have been translated from the Greek manuscripts, or in some cases, from a previous Latin or English translation.

Cloverdale Bible Way has translated the KJV into Chinese because they believe that the KJV best reflects the doctrines of the Message of William Branham. Rather than going to the original Greek and Hebrew manuscripts, they used an archaic English translation that is over 500 years old. How does that even make sense?

A Wycliffe Bible translator once told me that "the only thing worse than no scripture in your own language is badly translated scripture.” That is exactly what Cloverdale Bible Way has done and it is a sin!

Original Language of the New Testament

The New Testament was originally written in Koiné Greek (from κοινή, meaning "common"). Koiné Greek arose as a common dialect within the armies of Alexander the Great and was the common Greek dialect spoken in the eastern half of the Roman Empire at the time of Christ.

Original Language of the Old Testament

What Christians refer as the Old Testament, is what Jews refer to as the Tanahk. This was originally written in Hebrew on scrolls. The Tanahk was carefully translated into Koiné by Jewish scholars long before Jesus’ birth, for the benefit of the Jews who had scattered from Judea. The Greek version of the Tanahk is called the Septuagint or the LXX, which refers to the legendary seventy Jewish scholars that completed the translation as early as the late 2nd century BC.

Where did the KJV come from?

Who translated the KJV?

The translation work that was commissioned by King James 1 in 1604 was carried out by a group of 47 scholars, all of whom were members of the Church of England. The Old Testament was translated largely from the Hebrew Masoretic Text, and the New Testament was translated from what is now known as the Textus Receptus.

The Textus Receptus

The Textus Receptus came from the work of Erasmus, a Catholic priest, who compiled five or six very late Greek manuscripts dating from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries. Earlier, more accurate, manuscripts had not yet been discovered. The completed translation was first published in 1611, and became the third official translation into English. By the mid-18th century, this Authorized Version was the undisputed leading English version of the Bible. It underwent a revision in 1769, resulting in the text that is commonly referred to as the King James Version, even today.

Manuscript discoveries since the Textus Receptus

Over the last few centuries, since the publication of the original King James Version, many Greek manuscripts from as early as the second and third century have surfaced, showing the improved consistency and accuracy one would expect from much older manuscripts. In fact, it is widely believed amongst Bible scholars that this compilation of manuscripts is far superior, both in reliability and accuracy, to the Textus Receptus. Most translations completed in the last 100 years have made full use of the superior Greek texts, for both the Old and New testaments, and often use a hundred or more scholars, from many different church backgrounds, to ensure that the original meaning is faithfully transferred into the current English language.

How is the Bible translated?

Undertaking a translation is a gargantuan project, and the results are readily available to be critiqued by other scholars with knowledge of the original scriptures. This precludes doctrinal bias or other intentional “tampering” within Bible translations. To intentionally twist or change passages to accomplish a specific bias would be certain professional suicide for such scholars, and the idea circulated amongst some King James Only proponents that this type of manipulation happens regularly in modern translations is, frankly, steeped in ignorance.

Why do we need newer translation?

None of this information mitigates the impact that the King James Version has had in the Christian world. The King James Bible stands as perhaps the greatest literary work in history. It was a monumental and lasting achievement, and deserves to be, not only recognized as such, but should be preserved, read, and remembered. All of the evidence suggests that the translators who worked from 1604-1611 to complete the KJV did faithfully render the best available manuscripts (at that time) into an accurate and accessible English version for the English speaking world of the 17th century. However, this is equally true of the vast majority of the translations today; they have rendered the best available manuscripts into accurate and accessible translations for the English speaking world of the 21st century. We do not live in the 17th century. The inherent need for the written Word of God in the daily lives of Christians for instruction, and devotion, is as real today as it was in 1611, and deserves the accuracy and readability of a current translation. It is important to note, here, that the translators of the King James Version would have dearly loved to have had access to the superior early manuscripts available today, and equally important to note that, if living today, they would be translating the original Greek into modern, accessible English, just as they did then.

Is the KJV the only inspired English version?

So why do some Christians still insist on using the KJV, and only the KJV? For some, it’s as simple as a preference. The KJV is what they grew up hearing and memorizing, and nothing else sounds as regal, as authoritative as the KJV. Still other KJV only advocates believe that the Textus Receptus itself was especially inspired, and therefore the manuscripts on which it is based are divinely superior to the earlier manuscripts. The problem with this theory is that there is no solid evidence to support this claim and substantial evidence to the contrary. The Textus Receptus was copied much later, and not only has less overall consistency among manuscripts, but in addition, had a number of words added that do not appear in the earlier manuscripts. As it would be impossible to take away words that had not yet appeared in scripture, it is clear that the additional words have been added over the years. So those who subscribe to the Textus Receptus superiority theory are unwittingly usurping the divine inspiration of the original writers; Paul, Luke, Moses, etc., in favor of the idea that mere scribes copying scripture centuries after the authors penned them, possessed some additional, divine, insight from God; not exactly firm ground on which to stand.

Did William Branham believe the KJV was the only inspired English Bible?

Some message believers apply the following logic: if Brother Branham used the KJV, and he was vindicated of God, then, surely God was vindicating the version of the Bible that Brother Branham used.

But what did William Branham believe?

- In the studying of the Scripture, I have been accused, and do a great deal of typology. Which typology is typing the Old with the New. I'll tell you why I do that. It's because of this. Maybe sometimes the--the great words that scholars and so forth try to give the Bible Its--Its terms or pronouncing... I'm satisfied to take the King James for mine. It's waved the storms longer than any translation yet, and I just believe it that way.[1]

Though William Branham did preach and quote primarily from the King James Version, he never claimed the King James Version was the only real Bible, and in fact, used several different versions, including the Darby Translation, and the Amplified Bible. His quote above simply states that he was satisfied to keep the KJV, because it had stood the test of time. That is a personal preference, and, especially in 1953 when he said it, an understandable position. Regardless, the Bible itself did not need vindicating, by William Branham or anyone else. Christians have always, and will always, believe the original manuscripts to be the divinely inspired and authoritative Word of God. Therefore, any faithful translation into English is, by definition, also the Word of God. So what constitutes a faithful translation?

There are a number of translations available today, that are not only much clearer to read, but also more faithful to the original texts than the King James Version.

What is the best Bible translation?

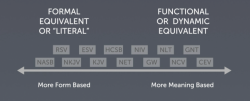

Translations may be located anywhere between the two poles of formal equivalence (word for word) and dynamic equivalence (thought for thought). Click on the chart to the left to get an understanding of where various translation lie.

A strictly literal translation would be largely unintelligible, but traditional translations, such as KJV, RSV, and NIV, have tended to translate sentence structures and figures of speech literally. These are usually perceived as intelligible and often normal, if sometimes a bit unusual for English. Dynamic equivalence (NLT, GNT) makes little if any attempt to preserve original sentence structure, but seeks to state the meaning of the text in natural contemporary idiom. Original metaphors may be retained if their meaning is clear to a contemporary readership. Today it seems clear that both types of translations have their place. Formal equivalence versions are convenient for deeper study, dynamic equivalence for day to day reading.[2]

It is interesting that the King James translators faced all the same resurrected issues that modern translations are faced with. There were those, for instance, who felt that a new translation implied that the church had been without the Word of God until then. In the preface already quoted the translators report their critics’ concerns.

- Hath the Church been deceived, say they, all this while?… We hoped that we had been in the right way, that we had had the oracles of God delivered unto us.… Hath the bread been delivered by the Fathers of the Church?… Was their translation good before? Why do they now mend it? Was it not good? (p. xvii).

Their reply was that,

- We do not deny, nay, we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English set forth by men of our profession … containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God: as the King’s speech which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the King’s speech, though it be not interpreted by every translator with the like grace, nor peradventure so fitly for phrase, nor so expressly for sense, everywhere.… No cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it (p. xix).

If, even the “meanest” (lowest in quality) of the existing translations could be rightly called the Word of God, to what purpose did the King James translators attempt yet another one? Here they actually quote Jerome (“Hierome” is their spelling), among others, as a worthy example for their own approach of returning yet again to existing Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. They respond to the question of “what they had before them” when they translated the Authorized Version.

- If you ask what they had before them, truly it was the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, the Greek of the New. These are the two golden pipes, or rather conduits, wherethrough the olive branches empty themselves into the gold. Saint Augustine calleth them precedent, or original, tongues; Saint Hierome, fountains. The same Hierome affirmeth, and Gratian hath not spared to put into his decree, That as the credit of the old books (he meaneth of the Old Testament) is to be tried by the Hebrew volumes; so of the New by the Greek tongue, he meaneth by the original Greek. If truth be to be tried by these tongues, then whence should a translation be made, but out of them. These tongues therefore (the Scriptures, we say, in those tongues) we set before us to translate, being the tongues wherein God was pleased to speak to his Church by his Prophets and Apostles (p. xxiii).

In addition, the King James translators included in their margins alternate translations for words or expressions whose precise meaning was unknown to them despite their diligent consulting of every text and translation available. They anticipated that this practice of giving multiple translations would be unsettling to some.

- Some peradventure would have no variety of senses to be set in the margin, lest the authority of the Scriptures for deciding of controversies by that show of uncertainty should somewhat be shaken (p. xxiii).

But their own view was that the variety of translations was good, not evil. In support of their position they quoted Augustine, who had said that “variety of translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures” (p. xxiv). And they argued that it was better not to dogmatize about some of the uncertain words of the original languages.

- There be many words in the Scriptures which be never found there but once, (having neither brother nor neighbor, as the Hebrews speak) so that we cannot be holpen by conferences of places. Again, there be many rare names of certain birds, beasts, and precious stones, &c. concerning which the Hebrews themselves are so divided among themselves for judgment, that they may seem to have defined this or that, rather because they would say something, than because they were sure of that which they said, as S. Hierome somewhere saith of the Septuagint. Now in such a case doth not a margin do well to admonish the Reader to seek further, and not to conclude or dogmatize upon this or that peremptorily? (p. xxiv).[3]

- ↑ 53-0325 ISRAEL.AND.THE.CHURCH.1_ JEFFERSONVILLE.IN

- ↑ Roger A. Bullard, “Bible Translations,” ed. David Noel Freedman, Allen C. Myers, and Astrid B. Beck, Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 2000), 183.

- ↑ James B. Williams and Randolph Shaylor, eds., From the Mind of God to the Mind of Man: A Layman’s Guide to How We Got Our Bible (Greenville, SC; Belfast, Northern Ireland: Ambassador-Emerald International, 1999), 77–79.